Monday, 12 February 2007

The Female of the Species

So who's kidding who? Like hell she is! All the most powerful and fiery qualities are focussed in Thai womanhood for which I salute and celebrate them. It is they who will fight most furiously for their young and for their families and for this strength of character as much as for their undoubted feminine qualities I admire them. Who is it who drinks all the lao khao then?

It sometimes happens that when I say "Thai girl', people think I've said 'tiger'. How apposite that is!

Had William Blake made it to Nana Plaza before going to London zoo, his famous couplets might possibly have run something like this.

"Thai girl, Thai girl, feisty, fit,

In the sois of Sukhumvit.

What immoral hand or eye

can frame thy fearless symetry."

Just an idle thought!

Saturday, 10 February 2007

Cat on a Hot Granite Rock

Some Venerable Antiques!

The locals hardly seem to use furniture and always sit on the floor, so why shouldn't I. And though traditionally the cart was always kept in the space under the house out here in Isaan, as it still is in Cambodia, my folks do all think me slightly mad keeping it there. Mama looks sadly at it... wouldn't even make any decent charcoal. Some of our visitors run their hands nostalgically over it, but the younger ones want to paint it or turn it into a table and put it outside in the rain.

Over my deadbody, say I as, in my view, this is a top quality artefact in fine condition, with its superb craftsmanship and decorated detailing, worthy of a serious museum. It's staying inside safe and dry if I have anything to do with it, as I insist on conserving it properly for later generations of Thais. If I succeed in this, I'll have done something important in saving a scrap of their heritage for them until such time as they actually learn to appreciate it. Sadly, the children round here have never seen a buffalo cart before and while they can utter the magic words, 'Toyota D4D Hilux Vigo' and 'Isuzu D-Max', this ancient form of transport is just simply too old and ridiculous for them.

The construction of my cart is at the very pinnacle of traditional evolved technology. I shall not bore you with details of its modular construction, that it anticipates by many centuries the profile of the leafspring and the rear subframe of Alex Issigonis's original Mini, but suffice it to say that the exact same cart could have been built both at Ankor a millennium ago or in Cambodia yesterday. The carts on the low reliefs at Ankor Wat are identical to it in every detail, even down to the number of spokes in the wheels. Then when I was in Battambang in Cambodia, I asked the price of a brand new cart and I was told how much... it was almost exactly what I paid in Buriram for mine.

The delightful man who sold it to me makes a living breaking up carts and making them into kitsch tables and chairs and garden pavilions. He has a massive yard with tens of men working, bringing the carts in from Cambodia, I guess, and competently destroying the remaining vestiges of heritage that every Thai should proudly cherish.

I see little around here in Isaan that counts as fine decorative art, craftsmanship or handicraft. I could single out the art of silk weaving and the making of fish traps and suchlike from bamboo.

In the National Museum in Bangkok there is a model of a cart from Si Saket which is identical to mine, but there is no example of a full sized cart on display. At the Siam Society in Asoke there is a fine one standing outside in the rain, but I see few if any elsewhere and those I do see are often in a poor state of repair.

I shall therefore look after mine faithfully as we antiques must stick together, even if in my case I risk charges of eccentricity and perhaps of something worse. Come to think of it though, in the catalogue of mild derangements what could be much sillier than blogging?

Of Walls, Wives, Caves and Gates

So what's the deal, this funny experience of ending up happily entangled with a Thai 'girl' young enough to be your daughter? How does it work exactly?

First of all she clubs you down with her consummate charm, then she grabs you by what remains of your greying hair and she drags you off to her cave. Well actually, maybe quite willingly you will walk, run to the cave even. But having got there and having decided to stay, your obligation is then to get out a-hunting... to provide the means of survival in a harsh environment for your lady and all those near to her. That's how it always used to be with marriage before the days of Germaine Greer, the condom and equal earnings for guys and dolls... and that's how it still is here. And there's nothing so extraordinary about that. She's not with you for the purity of your intellectual ability and you can't expect to discuss Nietsche and Kant or the romantic poets over the som tam and soda. It's not necessarily that she's not your intellectual equal... it's also the inevitable language barrier.

Whenever I meet some poor farang guy alone and palely loitering through the lofty aisles of Big C and I ask him what he's doing in these parts, invariably he'll say he's building himself a house. By which he means of course that he's building a house for his Thai girlfriend and her family! Is it going to be expensive I ask him and here he glazes over. Frankly he simply doesn't know yet.

What I daren't tell him is that although there are no lawyers' fees for buying the land (and so nothing to prove ownership), there will be a number of other substantial and unexpected expenses. First, come the rains, lest the house ends up knee deep in water, he'll have to spend good money bringing in tens of tons of soil to displace the monsoon floods onto his neighbours' land. Next he'll have to provide the rice farmers doing the hard slog of construction with iced water during the day and something much stronger such as lao khao at night. Then when it's finished he'll have to throw a three day house warming party during which he'll keep half the province fed and happily inebriated for at least three days, accompanied by ear-splitting music starts at four in the morning.

And last and certainly not least of the costs, he'll have to build a big, big wall all the way round the 'garden'. This will be unnecessarily high and made of cement rendered blocks, usually painted a pale colour so that it discolours with the rains and has to be repainted every year. It will probably be built before the house is started because it's very important, and it could cost as much as or even more than the house itself. Often the poor farang gives up on the whole affair, having only built the wall and having run out of money and romantic energy and endurance. Or he starts building the house but runs out of cash having only completed the roof. (At this point it should be noted that while in most normal places the roof is put on last, in Thailand it is common to do it first.)

A final shock expense is that at the front of the house, as the ultimate statement of vulgar opulence there must be erected a deeply embarrassing wrought iron gate of Buck House proportions. It will be a tall and elaborate confection of uprights and twiddly bits with little gold arrows on top that is totally unrelated to any concept of reasonable utility. Not least of the problems, it'll need constant repair and repainting which, true to tradition will never be done... Thais just don't do maintenance... and accordingly it'll degenerate into a dusty, rusty mess in a matter of months.

People ask me what are the biggest stresses in this my marriage and I always answer the same... it's 'the wall'... or to be more correct the absence of one. A few years back when I was digging my toes in about not building a wall and Cat was threatening to leave me to look for a less mean and unreasonable farang, (I think she was joking!), we compromised on a fig leaf of a wall at the front only but with concrete posts and chicken wire, topped off with barbed wire around the back. So that's what we finally did and I, at least, think it works very well indeed. I thus thought the matter was now settled once and for all, but in our most warm and intimate moments, Cat cannot restrain herself from gazing into my eyes and sweetly saying, 'Teerak, I want one more thing to make me happy jing jing.' I block my ears and turn a stony face. Not the wall again!

Is it possible for the farang outnumbered as he is, ever to win? Well, I admit I gave in cravenly on the big issue of the gate and there it now is in all its glory at the front of the house. For a dusty soi in a poor rice village in Surin, it really is a bit outrageous when others are living in hovels. Nor is it very functional. It's pretty difficult to open it as it's so heavy, bits keep needing to be welded back on and, Forth Bridge-like it needs constant repainting. I'm determined to keep it decent just to show the locals you should... and I've even been known to wield a paint brush myself and perhaps occasionally to feel a few swellings of secret pride at it's showy splendour.

There's one thing though I forgot to mention about this and other Isaan palace gates, namely that it's customary always to leave them wide open! To do otherwise would make it look as if you and your massive walls and gates are actually intended to exclude old friends who have always been used to freely wandering in since time immemorial.

Nobody could thus possibly suggest that these walls and gates serve a useful function. So do I mind this extravagant madness that allows more than a little farang money to trickle down, should I say cascade into the community where I now live? Of course I don't, perish the thought! If I did they'd all call me kee nieow... which means I'd be 'as mean as sticky shit', and for the resident farang that would be the end, a social fate worse than death.

Thursday, 8 February 2007

An Expat Expatiates

I guess I’m an expatriate as I live in Surin with Cat, though as I scribble this in my notebook, I’m gazing out at the mist and rain that’s been sweeping across the Tamar valley in the west of England ever since we arrived here six days ago. We’re staying with our old friends, Peter and Laylai who live most of the year just across the border from us in Si Saket, though when we visit England, we usually get away to see them if they’re in Cornwall. As Peter’s an expat too, he’s the only person who can truly understand me; other regular beings think me slightly deranged.

In Surin, especially in the dry season, I do sometimes miss England. I long for marmalade on brown toast and even the Sunday Times.

Even in Bangkok I cannot always restrain home thoughts from abroad, standing bent double on a noisy green mini-bus as it terrorizes Sukhumvit soi 71. “England, with all thy faults I love thee still.” Though now in England in early summer, I’m missing the passion of a tropical downpour as I watch the grey, depressing variety that’s dribbling endlessly down outside the window.

Slightly bored, I pull Peter’s battered Universal Dictionary of the English Language, thirteenth impression, 1960, off the shelf and aimlessly look up ‘expatriate’. Interestingly it’s not shown as a noun, so ‘an expatriate’, a rootless, beer-soaked drifter in baggy shorts, is a new usage, a product of globalization perhaps. But it lists the verb, ‘to expatriate’, meaning, ‘to drive out, banish a person from his (sic) native land.’ So we’re exiles who’ve been driven out and banished, are we?

There are, of course, many reasons we expatriate ourselves, be they world weariness, the weather, women and occasionally work. But while I’m not an ex-patriot and still love my country, I’ve voluntarily chosen to live in Thailand because I love it too. I love the constant stimulus of living in a different culture, the lure of the exotic and the fact that being a farang makes me a little exotic too. My pallid skin and proboscis nose at last are truly appreciated.

In England I only have to open my mouth and everyone knows my origins, but in Thailand I can be more myself. Here I’m a farang, a high status term with a tinge of abuse, though I’m categorised mainly by the state of my wallet. Am I unusually wealthy or merely rich? Generous, or mean as sticky shit? No, you can never escape being pigeon holed.

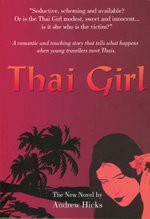

Thailand’s the second expat page in my life as ages ago I lived and worked in Nigeria, Hong Kong and Singapore. I can’t seem to kick the expat habit because I enjoy being slightly detached, being a spectator, a student of the society I find myself in. And in this it seems I’ve become a pro; my recent novel, “Thai Girl” is already a bestseller, credited, wrongly I’m sure, with special insight into the interaction between farang and Thais.

But it’s not all good and being an expat anywhere in the world involves constant compromise, irritations too. In Thailand I’m illiterate; I can neither read nor write. And however hard I work on my tones I might as well be deaf and dumb for all my linguistic efforts. Every other language has different words for ‘dog’ and ‘horse’ and ‘near’ and ‘far’, so why can’t the Thais? Is it to confound the foreigner?

And I’m not supposed to get cross when I’ve no idea what they’re all banging on about, keeping me in the dark. The boy in the bank can’t understand a thing I say, the taxi’s going half way round the world, and my order isn’t ready as promised; it’s broken and scratched, it’s the wrong size and the wrong colour. But never mind, mai pen rai, they tell me as they take my money. Laugh it off, hot head, don’t be jai rawn. And don’t raise your voice, you might upset us.

But it’s too bloody hot, the sweat’s gluing the shirt to my armpits, and worst of all, I can’t express my frustration. Sometimes it’s hard keeping the lid on.

Yes, there are frustrations in the expat life and we never hesitate to complain about them, especially to other expats. From Dubai to Delhi and Rio to Riyadh, we sit at the bar, whingeing into our beers. As you can’t complain to the locals, you need a safety valve, so we grumble to each other.

Back with Peter’s dictionary, the other word I was looking for was the verb, ‘to expatiate’. It’s got nothing to do with expats, but to my delight, although ‘expatriate’ and ‘expatiate’ come from different Latin roots, the meaning of ‘expatiate’ is curiously appropriate. ‘To expatiate’ means ‘to dwell at length, to speak at length upon’. Hence, to rant and ramble on, to bore the pants off. It’s exactly what we expats like doing, expatiating about everything that makes us mad.

And maybe that’s why I bore my friends when I visit England. They don’t listen when I tell them about Thaksin’s ‘rent a cow’ scheme, the million baht fund or the exotic buffet at the Chiang Mai Night Safari Park. So I drive down to Cornwall to see Peter and we sit in his window with a beer or two and look out at the Cornish mist. And though we’re at home, we expatiate our fill because that’s always an inescapable part of being an expat.

There Go the Mango Trees!

It was over a year ago that a wizened little old man came and started cutting down the two great towers of bamboo that stand just outside our far boundary which nicely screened us from the next farm house. I went down to talk to him as he toiled away and he told me that next in line for the chop was the three big mango trees next to the bamboo. “They’re too old and they’re going to die anyway,” he said.

I asked him what he was going to plant in their place. “Mango trees,” he told me.

Appalled, I mentioned this awful prospect to Cat but she didn’t seem unduly bothered.

“It’ll spoil all the greenery we see from the house and open up the mess of the house beyond,” I complained. “Couldn’t we offer him something to leave them standing?”

Cat was appalled at my suggestion. “Cannot,” she said. “Graeng jai! Must think of him… let him do what he wants. Anyway, this old man very rich… not need your money… have seven cows!”

“But he’s as old as the hills and I could save him the sweat of doing all that work and save the bamboos too,” I pleaded without any success. But I’m only a farang, an interloper in a Surin village whose small affairs will flow whichever way without any stirring from me.

Then to my relief he didn’t cut down the mangoes and perhaps because the price of sugar is buoyant with the new market in ethanol fuels, he planted sugar cane instead. Now almost a year later this has been harvested and the land is bare. Although you can get a further crop from canes that have been cut, it looks as if they’re clearing the land for something else, perhaps returning to the original plan for more mangoes.

Now, today I stood on my upstairs verandah as the first mango tree screamed in pain and plunged to the earth with a mighty crash. Kicking up a cloud of dust, its earthy smells wafted back to where I was watching from the house. I then continued writing at my laptop as they cut at the second tree until I knew its time had come and watched it too plunging earthwards, kicking a big hole in the greensward that surrounded our land. Though it now gives us a glimpse of the rice fields beyond, I’m glad that for some reason they have so far spared the third mango tree the same awful fate.

Looking down at our terrace and at the dry, grassy slope beyond, there’s the usual party in full swing consisting as always of mothers and babies, assisted by sundry old grannies. The house is never empty and we’re never alone. Everyone seems to have a baby, though there are few fathers around as they’ve either fled the scene or are away working in Bangkok. It’s mainly women and children and old men round here, and they’re pretty poor, though there are some compensations. With time and good company never in short supply, parties like this one are among them.

Sitting on the mat on the grass are Cat’s Mama, a sweet and gentle woman who has heroically raised seven children, together with Cat and a couple of girlfriends and an old soul of eighty one who seems to be the centre of attention. She can hardly walk but as she is one of the elders, Cat sent for her and had her wheeled round on our rot ken or push cart. She sits thoughtfully pounding betel leaves and lime in a tiny pestle before wrapping a slice of betel nut and placing it in her cheek. This ritual is unvarying and essential and clearly a great comfort to the older folk of my vintage. Cat tells me she was a teacher and that she came to the area with her husband when there were tigers and elephants at large to clear the forest for rice fields. The sheer scale of the work and of ploughing and growing rice without mechanical assistance leaves me breathless with admiration.

The old couple survive with great dignity but life has had its setbacks. They had five daughters and though all married only one of the husbands is still alive. The four have since died of diabetes, liver failure and unnecessary accidents. The sole surviving son-in-law is a likeable rogue who funds his lifestyle by selling off his wife’s rice land to pay the installments on his pickup. The old man wept when he told Cat how once he was rich but that now the family had almost nothing left with their rice land, the source of life and survival, all but gone.

This couple were two of the first people I met when first Cat brought me to the village to meet her family, me a strange and greying suitor for this energetic and captivating young woman.

She and I had transgressed by being together without formal sanction so now was the time for the elders to review our relationship, to predict our future and perhaps to bless our union.

Cat didn’t tell me what exactly was going to happen that night but made sure I was around when the four elders came and sat in a huddle on the floor at the back of the family house by the light of a naked light bulb. By the time I was called in to sit with them, there were some bits of dead chicken scattered around and they were all talking animatedly. One of them was the ancient teacher, now one of my favourite people, together with her bright eyed pixie of a husband. One by one they inspected the gizzard of the chicken and finally delivered their verdicts. There was much talk and waiing and tying of string on wrists, while I was left mystified as they hobbled away, not understanding a word of what had been said. My Thai was progressing quite well but it availed me nothing as they were speaking a babel of Lao and Suay.

“They say we okay,” said Cat, encouragingly. “Can stay together. Maybe later you go back to your own country but no problem, you and me, at least if I don’t talk too much.” I later got the picture that Cat had a reputation in the village. Her family called her ‘Pok-Pok’ and at school she was called Gas, for exactly the same reason. Four years later she and I are still together and the truth is that I still love her for talking too much. And as I stand on the upstairs verandah looking at the little party playing out on the mats below me, yes I can certainly hear that Cat is contributing well to the conversation. But then so she should be. She now has the best house in the whole village and is a notable personality much to be reckoned with.

It’s strange though that nobody seems the slightest bit bothered about the sad loss of the mango trees. Perhaps they’ll yield some good charcoal and a bit of extra land for cultivation. They look at me as I complain at this unecological vandalism, eyeing me and thinking, “What’s the farang making all the fuss about this time?”