The Chinese town of Shiping seen from the gate is like any other.

Modern cars and mobiles contrast with the old back streets.

The daily grind goes on as a woman washes dishes in the street.

And others wait in the early morning selling peanuts and oranges.

A lady barbecuing breakfast tofu looks more animated though.

While a food seller stoicly waits eternally for sales.

The streets are busy, though what are they laughing at?

Street life is open and public and privacy is not much valued.

The railway station where Jack Reynolds arrived in 1947.

A rainy street scene in an old village near Shiping.

Roofs of an ancestral temple epitomise old China.

And a fret work window makes another classic image.

Old men play old mens' games in the warm of one of the rooms.

These two take the money to see inside the courtyard house.

Meanwhile, Denise photographs a fine interior.

A detail on a carved door suggests the opulent life of the few.

An ancestral hall, built to commemorate the rich forebears.

Family and friends await a lavish wedding breakfast.

The wedding food looks distinctly appetising.

This fine house is remarkable for being built of mud bricks.

The interior is spacious and elegant but today is just a farm house.

Word is going around Shiping in Yunnan province in western China that when the foreigners have difficulty negotiating an important matter of personal relations, they reach a decision by the strange practice of tossing the condom.

Over the Chinese New Year, we were on holiday there (See the two blog articles below.) and had just arrived at Shiping. This is a typical small town that promised us some traditional architecture, and we’d found our way to a clean modern hotel in the town centre. The problem was that they only had two rooms that were very different, a slightly gloomy one on the ground floor and a more pleasant one that demanded a climb up four flights of stairs. So who was to have which room?

The receptionist looked on as we debated and dithered. Then Bill suggested we toss a coin. Trouble is, they don’t seem to have coins in China. We could toss something else then, but what? The girl looked mildly aghast when we used the one thing that’s beside the bed in every hotel in China, which duly made the decision for us. I’m not surprised if she later told all her friends about our bizarre behaviour.

Shiping is famous for making tofu and its present wealth is based on tofu factories, big and small, which are everywhere. Even half a century or so ago it was an unusually rich town but that was when the local tin industry was flourishing.

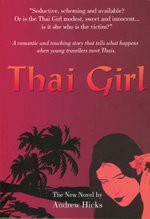

Jack Reynolds, the Bangkok based novelist, whose fascinating life story I’m hoping to write, was in this region of China in the late forties doing transportation and relief work. He was working with the Friends Ambulance Unit and was sent by them to Shiping to investigate an outbreak of malaria. He arrived by train, alighting presumably at the impressive French built railway station that we saw, which still stands at the end of the line exactly as it must have been in his day.

On coming into the town Jack was struck by how very prosperous it was.

“Plodding around I quickly realised that Shihping was the most prosperous town I’d ever visited in China. In the main streets the temples were tumble-down but the markets were stuffed with food and goods. But it was the side streets which were the revelation. They were incredibly quiet and empty for Chinese streets. They were lined on both sides by high stone walls. At intervals in the walls there were roofed gateways adorned with some of the best stone carving I ever saw in China. Behind these gates the tin mine owners lived in vast compounds built on the traditional plan – a succession of four courts joined by moongates. You were always asked inside the main gate, asked to sit in straight-backed chairs in a reception room just inside, and provided with tea and sunflower seeds.”

The shocking truth though was that this wealth was built on slave labour and child labour at that. In a fine article in the Bangkok Post in 1977, which I hope to include in my forthcoming book, Jack exposed the awful story that the miners were all little boys because they were small enough to move through the low galleries of the mine. To stop them getting too big they had an inadequate diet and were given opium to keep them going. Working in these appalling conditions, their life expectancy was about two years.

For his persistence in investigating and visiting the mine, Jack very nearly paid with his life. A serious attempt was made to kill him.

The arrival of the communists a few years later put an end to all this, but now, more than half a century later, on seeing some of the fine buildings in the town it constantly struck me that while they truly are beautiful, the ostentation and display of their owners was built on the bones of small children who never had a proper life.

Today most of the old buildings in the town have been swept away though and Jack would recognize little in the town other than the railway station. For tourists like us wanting to find old ancestral shrines and courtyard houses, you thus have to go out to surrounding villages. Nonetheless, despite China having moved confidently into the twenty first century, I’m sure that the feel of the place would be familiar to Jack. The people, though now better off, are still much the same as ever. The experience of eating breakfast out on the street in the chill of the morning, sitting on stools six inches high, cannot have changed one bit. And the food would be familiar too, even if tofu has edged its way onto the menu. The light, the mist, the smells, the mud… all these things in China are eternal and unchanging.

After exploring the town centre, we took a day trip out to a village called Zhengying Cun which is about ten kilometers to the west and is known for its fine domestic architecture and temples.

As always, once out of the town, it was apparent that China has a huge appetite for steel and for vegetables; there were factories of some sort scattered everywhere and tight between them sprawling acres of vegetables.

As you drive along motorways and side roads, in valleys and villages, between houses and commercial premises everywhere you see row upon row of vegetables. The Chinese ability to grow vegetables in abundance is remarkable. Every inch of ground must be fully exploited and to this end their vegetable gardens are incredibly neat and orderly. I have the feeling though that this strict imperative exhausts the national capacity for tidiness and, apart from their modern townscapes, rural China is often a chaotic mess. On the way to the village for example everywhere on the side of the road were sprawling heaps of coal just dumped untidily by its owner. If tidiness doesn’t make money, then it’s not worth bothering about.

When our taxi reached the village it began to pour with rain. That’s the end of any decent photos, I thought. Even so, as we walked on through the drizzle, I was optimistic that misty grey skies and wet pavements would evoke China as it so often is. Certainly the traditional buildings did not disappoint. What was so pleasant was the relative absence of vehicles as the whole place had a human scale with small paths and passages between the buildings with their pan-tiles swept up roofs. It had not been planned around the motor vehicle.

We were able to visit a number of fine ancestral halls and courtyard houses and they were superb. In one of the halls there was a wedding feast in full swing and it was fun being a fly on the wall as food was carried from the kitchens to the tables where the friends and family were sitting at tables. Certainly we attracted a few curious glances but generally we passed largely unnoticed as foreign tourists are no longer a rarity.

The house I liked the most was at the end of our walk, a large and elegant building whose fine quality was not diminished by the fact that it was made of mud brick. We had a nose around inside the courtyard and it was apparent that this was no longer the home of a rich, capitalist road landlord type but of modest ordinary people. Yet despite relative neglect it looked strong and was surviving the years well despite its form of construction, which is a tribute to its builders.

Our visit over, I hardly believed that the promised bus would actually arrive as it was getting late and we were well off the beaten track. Should we walk therefore or should we wait? Could we phone for a taxi? We seemed to be at odds over what to do. How therefore would we resolve this awkward impasse between us.

The light was fading and I was trying to think it all through. If we could narrow the options to two and if there were a pharmacy nearby we could buy what we needed to give us a final decision. But by this time everything was now closed.

Then thankfully there was a hoot and a bus came round the corner to take us back to Shiping.

Perhaps in future I should carry a packet with me to deal with situations like this, though explaining the reason to my wife, Cat, might be a little bit difficult. I’m not sure she’d believe me.

Andrew Hicks The “Thai Girl” Blog March 2010

4 comments:

Great photos

REALLY great photos you got here. The old style houses and the Chinese atmosphere around is so different from example Thailand cause of climate and things. Very good blog. Thanks.

Great Photos. All those vegetables? Turns out they are being shipped to America... as organic foods. Whole Foods, an upscale health food store chain here in the US, has had exposed that alot of the produce and frozen vegetables are from China. And labeled organic. Even the California organic mix stir-fry. Do they REALLY qualify as organic? Love your reports from abroad as well as Thailand. Thanks.

You built up a great picture in my mind of this adventure into Shiping and the photos were a lovely bonus.

Next time you're there photograph those vegetable rows, please.

Post a Comment